Despite the few days remaining until the long-awaited end of this unprecedented year, we unfortunately know that there is no magic spell that will make the COVID-19 pandemic disappear when the clock strikes midnight. We are now busy waiting for an effective worldwide vaccination campaign that will allow us to go back to our daily routines – what we used to call “normality”-, while governments continue to contend with a relentless spread of the virus and its harsh impact on society. But, since the 2019 novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 has come to stay, it got me thinking: what will happen next?

My name is Sara Feijoo Moreira, PhD Candidate at KU Leuven investigating in the European H2020 MSCA-ETN InnovEOX project and this is my personal contribution to the InnovEOX blog series. Spoiler alert: I do not have the answer to that question. Nonetheless, what I do know is that science and research are the key to knowing more about this virus and developing strategies to mitigate its effects. In order to live with this pathogen in the coming years, we need to learn how to keep it under control, not only in terms of medical treatment, but also in all other areas where it is present. One of these areas is water and wastewater treatment, which is very much close to the core of our InnovEOX focus, as our work is aimed at addressing the contamination of water resources by emerging contaminants.

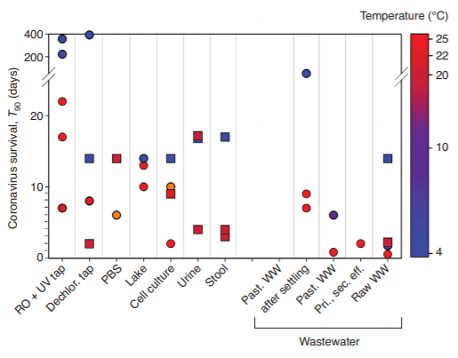

Figure 1. Survival time of SARS-CoVs (squares) and other enveloped viruses (circles) for 90% inactivation (T90) in water samples including: deionized and sterilized tap water (RO + UV tap); tap water after chlorine removal (Dechlor. tap); phosphate buffered saline solution (PBS); lake water and human excretions (urine and stool); pasteurized (Past.) wastewater (WW) after settling; past. raw WW; primary or secondary effluent (Pri., sec. eff); and raw WW [1].

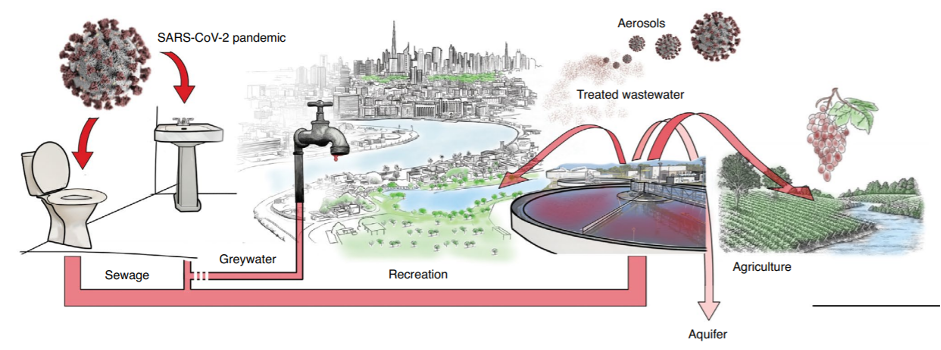

Coronavirus-containing water can affect humans, not only by drinking it directly, but also through its use for agricultural and recreation purposes, or even its aerosolization in the droplets from shower heads [1, 2]. It has been postulated that treated water effluents may therefore be a route of infection for SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks, especially given the higher viral load in wastewater during pandemic times and the fact that there is no evidence that conventional wastewater treatment technologies (which rely on disinfectants such as chlorine and ozone) can provide a complete virus removal [1, 2, 4].

Figure 2. Overview of potential SARS-CoV-2 dissemination in industrialized countries [1].

References

[1] A. Bogler, A. Packman, A. Furman, A. Gross, A. Kushmaro, A. Ronen, C. Dagot, C. Hill, D. Vaizel-Ohayon, E. Morgenroth, E. Bertuzzo, G. Wells, H. R. Kiperwas, H. Horn, I. Negev, I. Zucker, I. Bar-Or, J. Moran-Gilad, J. L. Balcazar, K. Bibby, M. Elimelech, N. Weisbrod, O. Nir, O. Sued, O. Gillor, P. J. Alvarez, S. Crameri, S. Arnon, S. Walker, S. Yaron, T. H. Nguyen, Y. Berchenko, Y. Hu, Z. Ronen and E. Bar-Zeev, “Rethinking wastewater risks and monitoring in light of the COVID-19 pandemic,” Nature Sustainability, vol. 3, pp. 981-990, 2020. [2] V. Naddeo and H. Liu, “Editorial Perspectives: 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): what is its fate in urban water cycle and how can the water research community respond?,” Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology, vol. 6, no. 5, pp. 1213-1216, 2020. [3] D. A. Larsen and K. R. Wigginton, “Tracking COVID-19 with wastewater,” Nature Biotechnology, vol. 38, pp. 1151-1153, 2020. [4] M. Kitajima, W. Ahmed, K. Bibby, A. Carducci, C. P. Gerba, K. A. Hamilton, E. Haramoto and J. B. Rose, “SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater: State of the knowledge and research needs,” Science of The Total Environment, vol. 739, p. 139076, 2020. [5] G. Medema, L. Heijnen, G. Elsinga, R. Italiaander and A. Brouwer, “Presence of SARS-Coronavirus 2 RNA in Sewage and Correlation with Reported COVID-19 Prevalence in the Early Stage of the Epidemic in The Netherlands,” nvironmental Science & Technology Letters, vol. 7, pp. 511-516, 2020. [6] W. Randazzo, P. Trunchado, E. Cuevas-Ferrando, P. Simón, A. Allende and G. Sánchez, “SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater anticipated COVID-19 occurrence in a low prevalence area,” Water Research, vol. 181, p. 115942, 2020. [7] L. Casanova, W. A. Rutala, D. J. Weber and M. D. Sobsey, “Survival of surrogate coronaviruses in water,” Water Research, vol. 43, no. 7, pp. 1893-1898, 2009. [8] T.-T. Fong and E. K. Lipp, “Enteric Viruses of Humans and Animals in Aquatic Environments: Health Risks, Detection, and Potential Water Quality Assessment Tools,” Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, vol. 69, no. 2, pp. 357-371, 2005. [9] K. R. Wigginton, Y. Ye and R. M. Ellenberg, “Emerging investigators series: the source and fate of pandemic viruses in the urban water cycle,” Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology, vol. 1, pp. 735-746, 2015.

Sara is an enthusiastic Chemical Engineer with a passion for sustainability, innovation and design. She comes from a small and cosy city in the north-west side of Spain: Santiago de Compostela. Currently, Sara is an Marie Curie Early Stage Researcher (ESR) for the InnovEOX project at KU Leuven and under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Raf Dewil. In particular, she is ESR1 focusing on developing optimized process conditions for the in-situ generation of sulphate radicals and subsequent organic degradation of emerging contaminants in water.

InnovEOX Innovative Electrochemical OXidation Processes for the Removal and Analysis of micro-pollutants in water streams

InnovEOX Innovative Electrochemical OXidation Processes for the Removal and Analysis of micro-pollutants in water streams